Investigation report

Scottish Parliament Region: North East ScotlandCase 201002867: Tayside NHS Board

Summary of Investigation

Health: Hospital; Care of the elderly The complainant (Mrs C) raised a number of concerns about the prescription of antipsychotic drugs to her aunt (Miss A) during her admission to hospital in September 2009 and that the prescribing chain of command of the drugs was Specific complaints and conclusions

The complaints which have been investigated are that the Board: (a) wrongly prescribed haloperidol to Miss A from 15 until 25 September 2009 (not upheld); and (b) failed to provide clarity surrounding the prescribing chain of command (not upheld). Redress and recommendations

The Ombudsman recommends that the Board: Completion date (i) carry out an audit of their practice on implementation of the Adults with Incapacity Act with particular reference to consent and report to the Ombudsman on the findings; (ii) amend its guidance on managing patients with delirium to include the requirements of the Adults with Incapacity Act; (iii) share this report with staff to ensure they complete documentation properly and meet the 14 December 2011 communication needs of patients with cognitive or sensory (or both) impairment; and (iv) apologise to Mrs C for the failures identified in this 16 November 2011 The Board have accepted the recommendations and will act on them 16 November 2011 Main Investigation Report

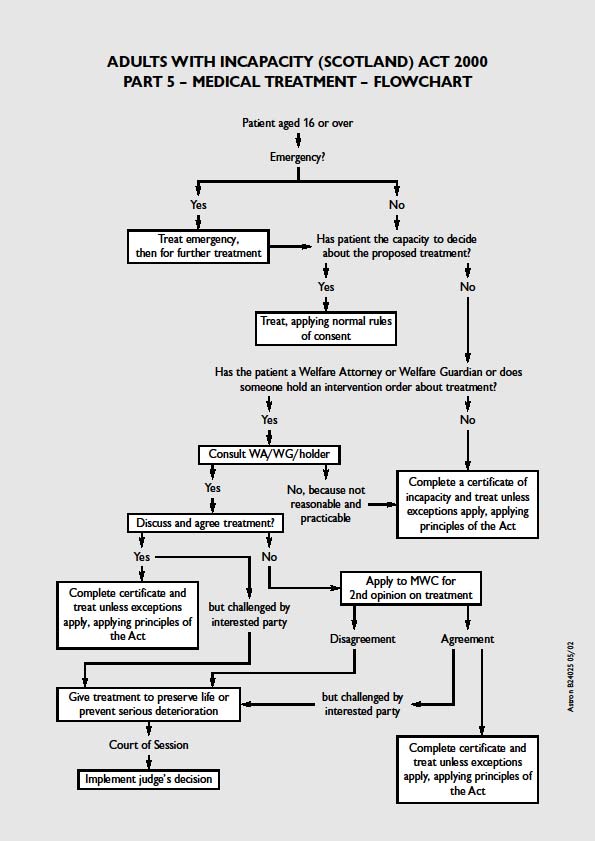

Mrs C has complained about the care and treatment provided to her aunt, Miss A, by Tayside NHS Board (the Board). On 2 July 2009, Miss A was admitted to Ninewells Hospital (the hospital) and scheduled to be discharged to another hospital on 28 September 2009. She had significant hearing impairment and required the use of bilateral hearing aids. Before her planned discharge, Miss A fell and fractured her hip. She was transferred to an orthopaedic ward and, following concerns about the deterioration in her mental state, prescribed lorazepam. She was then prescribed haloperidol instead of lorazepam from 15 September until 25 September 2009. Mrs C said Miss A's behaviour was due to her frustration at not understanding why she was in hospital and what was being said to her because of her hearing difficulties. Had the healthcare professionals communicated with and involved Mrs C in their assessment of Miss A and treatment decisions, then she would have spoken to Miss A and the medication may not have been necessary. Mrs C also complained about the lack of clarity from the Board surrounding the prescribing chain of command of haloperidol. As a result of the Board's failures, Mrs C said that Miss A had received unnecessary medication that had posed a risk to her 2. Mrs C complained to the Board on 3 November 2009. On 10 December 2009, the Board responded to Mrs C's letter of complaint. Mrs C met the Board on 10 February 2010 to discuss her concerns and received a further letter from them on 18 March 2010. Mrs C remained dissatisfied with the Board's responses and complained to my office on 28 October 2010. The complaints from Mrs C which I have investigated are that the Board: (a) wrongly prescribed haloperidol to Miss A from 15 until 25 September 2009; (b) failed to provide clarity surrounding the prescribing chain of command. During the course of the investigation to this complaint, my complaints reviewer obtained and examined Miss A's clinical records and complaint correspondence from the Board. She obtained advice from two of the Ombudsman's professional advisers: a consultant physician specialising in care 16 November 2011 of the elderly (Adviser 1) and a nursing adviser with extensive experience of psychiatric nursing (Adviser 2). I have not included in this report every detail investigated but I am satisfied that no matter of significance has been overlooked. Mrs C and the Board were given an opportunity to comment on a draft of this report. Relevant legislation Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000 (the Act) provide a framework for safeguarding the welfare and managing the finances of adults who lack capacity due to a mental disorder or inability to communicate. The Act sets out the principles to be followed by everyone who is authorised to act on behalf of someone with incapacity (a 'proxy'). In relation to decisions about medical treatment, the Act allows treatment to be given to safeguard and promote the physical and mental health of an adult unable to consent. Where a welfare attorney or guardian has been appointed with healthcare decision-making powers, the doctor must seek their consent where it is practicable and reasonable to do so. If the adult has no proxy, a doctor is authorised to provide medical treatment subject to certain safeguards and exceptions (see paragraph 8 below). The Act defines incapacity as being incapable of: acting on decisions; or making decisions; or communicating decisions; or understanding decisions; or retaining the memory of decisions. An adult may lack capacity because of mental disorder, such as dementia. In relation to medical treatment, in order to demonstrate capacity, an individual should be able to: • understand broadly what the treatment is, its purpose and nature and why it is being proposed; understand its principal benefits, risks and alternatives and be able to understand in broad terms what the consequences will be of not receiving the proposed treatment; retain the information long enough to use it and weigh it in the balance in order to arrive at a decision; and communicate that decision. Healthcare professionals who provide medical treatment to patients who lack capacity to consent should do so with regard to the principles of the Act. 16 November 2011 This means that healthcare professionals are required to complete a certificate of incapacity and should consult those with an interest in the person's welfare, such as the person's primary carer, nearest relative etc, whenever practicable and reasonable. A flow chart showing the steps healthcare professionals should take is at Annex 3. Clinical background Miss A was admitted to hospital on 2 July 2009 with a bowel obstruction. She had significant hearing impairment and required the use of bilateral hearing aids. On 16 July 2009, she fell and fractured her hip and was transferred to an orthopaedic ward. She had surgery for her fractured hip on 17 July 2009. The medical records noted periods of confusion and the results of a CT scan on 31 July 2009 showed substantial cortical atrophy and small vessel ischaemic change. On 21 and 22 August 2009, the medical records noted Miss A's increasingly aggressive behaviour. On 26 August 2009 a doctor prescribed lorazepam (a sedative drug). A psychiatric liaison nurse reviewed Miss A on 28 August 2009 and suggested that the dose of lorazepam should be reduced because it increased the risk of falls. The psychiatric liaison nurse noted a mini- mental state examination score of 6/30, but that Miss A appeared to perform better when the hearing aids were turned up. The medical records showed that the family queried whether the hearing aids were working on 30 August 2009 and that Miss A also raised this on 2 September 2009. On the same day a doctor suggested contacting the audiology department, but a nurse noted that this had not been done yet. A medical entry on 4 September 2009 noted that the audiology department suggested that the hearing aids had been sent to be 10. On 7 September 2009, the psychiatric liaison nurse reviewed Miss A and encouraged one-to-one nursing. On 15 September, the medical records noted episodes of poor compliance by Miss A, assaults on staff, wandering on the ward and interfering with other patients' belongings. During a telephone call, the psychiatric liaison nurse suggested changing her medication to haloperidol (an antipsychotic drug) twice a day plus one extra dose if required. The psychiatric liaison nurse reviewed Miss A on 17 September and noted that she was generally better and not over sedated. They acknowledged that not all episodes of concerning behaviour had been documented and suggested that they should be. They also suggested reducing the haloperidol if there was evidence of over sedation. On 21 September 2009, the records noted that Miss A wandered constantly but that her behaviour was not disruptive. An 16 November 2011 additional dose of lorazepam was given on 24 September 2009. It was noted that an additional dose of haloperidol was given on 25 September 2009 because she was more aggressive. Miss A was discharged from hospital on 28 September 2009. (a) The Board wrongly prescribed haloperidol to Miss A from 15 until

25 September 2009

11. Mrs C became increasingly worried about Miss A during her admission to hospital. Mrs C was concerned about Miss A's mental health and that she was becoming increasingly frustrated because she could not hear or, therefore, understand what was being said to her by healthcare professionals. Mrs C was shocked to be told by staff that Miss A had become disruptive and abusive and believed it was due to frustration. Mrs C raised concerns about the management of Miss A's hearing impairment and hearing aids by healthcare professionals (Miss A had been without her hearing aids for a week) and that this had exacerbated the problem. Mrs C was very concerned to learn that Miss A was prescribed haloperidol for her behaviour, which had posed a risk to her health. Mrs C believed Miss A's behaviour could have been addressed without haloperidol if healthcare professionals had involved Mrs C in the assessment of Miss A and treatment decisions. Mrs C said that Miss A improved significantly when she was transferred to another hospital where her needs had been met. Board's response 12. In their response, the Board said that Miss A's behaviour and confusion varied; sometimes she was disorientated and tried to mobilise without assistance and other times she was aggressive towards staff members and attempted to leave the ward. She would also try to touch other patients in order to help them. A CT scan carried out on 30 July 2009 showed that Miss A had been suffering a gradual deterioration of her faculties. She had also been suffering from a urinary tract infection which can cause or increase confusion in older people. On 15 September 2009, in response to concerns raised by staff about Miss A's behaviour, the psychiatric liaison nurse said that haloperidol should be prescribed instead of lorazepam. This was to settle Miss A and make her behaviour more manageable. The psychiatric liaison nurse frequently recommended the use of haloperidol to manage patients whose behaviour was challenging so that nursing care could be carried out. The Board said that the dose of haloperidol prescribed was in accordance with the guidelines in the British National Formulary. 16 November 2011 13. The Board went on to say that Miss A was assessed by the psychiatric liaison nurse on 28 August, 7 September and 17 September 2009 and that it would have been possible for Mrs C to have been present. The Board apologised that this was not offered. The Board also acknowledged that prolonged placement within an orthopaedic unit was not the best place to provide care to Miss A, but this was the only option due to the shortage of beds. 14. Referring to communication, the Board said that Miss A had found communication difficult because of hearing loss even though she had bilateral hearing aids. One member of staff had changed batteries on her hearing aid and other nurses checked to ensure they were switched on. The records also stated that the hearing aids were sent to the audiology department on 7 September 2009. The Board acknowledged that the matter had been very distressing for Miss A and apologised. They said that staff had been reminded to check patients' hearing aids daily and send for repair quickly and that they should contact the audiology department if there were problems. Advice received 15. My complaints reviewer asked Adviser 1 to consider the reasonableness of the Board's prescription of haloperidol to Miss A. Adviser 1 said that haloperidol was widely used for the short-term treatment of delirium and behavioural and psychiatric symptoms of dementia. Like other drugs used to manage agitation or aggression, it was not entirely risk free and should be reserved for situations where there was a risk that the patient will do harm either to themselves or others and after other non-pharmacological measures such as one-to-one nursing care have been tried (although non-pharmacological measures in busy acute NHS wards was exceptionally difficult). 16. Adviser 1 went on to say that in his view, based on the evidence from the medical records, Miss A was suffering from cognitive impairment caused by delirium (an acute confusional state) for some or all of her hospital stay. It was possible she also had underlying dementia predating her admission that would have made the occurrence of delirium more likely. All the completed formal screening tests for cognitive impairment and mental state screening tests in addition to the results of the CT scan strongly suggested that Miss A had cognitive impairment, which was recognised by staff from relatively early on in 16 November 2011 17. Referring to Miss A's deafness, Adviser 1 said he did not believe her actions and demeanour could be explained just by her hearing impairment. However, that view was understandable and cognitive impairment was exacerbated by sensory impairment. Attention to improved hearing can help to improve delirium and it was not clear from the medical records that all steps were taken to deal with Miss A's hearing aids properly, but this was often a source of great difficulty in acute hospitals. 18. Adviser 1 said that many aspects of the basic medical management of Miss A's cognitive impairment were reasonable and some were of a good standard. These included: simple reversible causes of impairment such as infection was sought; specialist elderly medicine and psychiatric nursing opinions were available and obtained; when sedative drugs were prescribed for agitation, these were of appropriate standard and type in appropriate doses, and the need to monitor for side effects of these drugs were stressed; and non- drug management measures such as one-to-one nursing was suggested. Adviser 1 said the choice of lorazepam and haloperidol by healthcare professionals was in line with current best clinical practice in the management of delirium and were prescribed because of a genuine and valid concern that Miss A was at risk of harming herself or others. However, there were other aspects of the medical management of Miss A that were not of a reasonable 19. Adviser 1 was critical of the documentation surrounding the use of lorazepam and haloperidol. When the drugs were prescribed, the documentation of the precise indications for the use of the drugs was poor and there was no documentation to show whether staff felt it necessary to seek the consent of Miss A (or a proxy decision maker) to treatment. Furthermore, there was no documentation to show that staff had considered Miss A's capacity to participate in decision-making or consent or both to the use of such drugs. It was Adviser 1's view that Miss A lacked capacity at the time the drugs were prescribed and documentation under the Act should have been completed. There was no evidence that healthcare professionals felt it necessary to complete such documentation and there was no certificate of incapacity in the medical records. In his consideration of the Board's guidelines on the management of delirium in adult and older in-patients, Adviser 1 said that while overall it was of good quality, it did not refer to capacity, consent, or the use of the Act, particularly when prescribing drugs. 16 November 2011 20. Adviser 1 was also critical of the documentation about Miss A's cognitive impairment. Although staff recognised Miss A had cognitive impairment, the admission nursing documentation failed to adequately direct attention to the possible presence of cognitive impairment and where such prompts were present in the documentation, these were either not completed or acted upon. The documentation of pre-admission cognitive function was also poor. This was significant because the detection of change in cognition was key to the identification of delirium. Neither was there any documentation of attempts to find the results of previous formal assessment of Miss A's cognitive function from previous hospital records or the general practitioner. The documentation of the family's views on the current and prior cognitive status of Miss A was unstructured and superficial. Moreover, communication with the family regarding the possible causes of cognitive impairment and their management was poorly documented and according to Mrs C may not have occurred at all. 21. In conclusion, Adviser 1 said that although he agreed Miss A was inappropriately placed for a prolonged period in an acute orthopaedic unit, a large proportion of patients in such units were and would continue to be elderly and many will have pre-existing dementia or peri-operative delirium or both. These problems may be present on admission or may develop or worsen over an in-patient stay. These units should, therefore, be fluent in the management of cognitive impairment, specifically: detection and diagnosis, communication with relatives and carers, use of appropriate legislation, assessment of capacity, non-drug treatment and appropriate use of drug treatment. 22. Adviser 2 said that a person has capacity if they are able to understand information relevant to a decision, can retain the information long enough to make the decision and appreciate the consequences of deciding one way or the other. The medical records did not support Miss A's capacity to consent being assessed prior to the prescription and administration of psychotropic drugs. She had shown evidence of at least intermittent periods of confusion and poor recollection of why or how she was admitted to hospital and poor short-term memory more generally. Her mental state was recorded as showing a gradual deterioration. This should have alerted staff to the possibility of impaired capacity and a formal assessment of capacity should have been made. It was Adviser 2's view that she very likely lacked capacity and the measures set out in the Act should have been implemented. 16 November 2011 23. Adviser 2 also said that there was no evidence in the medical records to suggest the care team were fully aware of their responsibilities under the Act and the psychiatric liaison nurse should have prompted the general hospital staff regarding their responsibilities. The clinical team did not seem to be aware of their obligations to assess capacity before prescribing psychotropic medication. He concluded that care fell below an acceptable standard in relation to this aspect of the complaint. 24. Referring to the communication with Mrs C and the rest of the family, Adviser 2 said there were failures despite the Board's documentation lending itself to effective communication. In this case, the documents had been ignored by staff suggesting a clinical practice failure rather than a systemic failure. Adviser 2 said effective communication between all parties involved in the person's care was critical, it should be planned and follow a consistent pattern where practicable. Relatives and carers should be viewed as partners in the care process, not bit part players. In this case, the involvement of relatives was inconsistent, unstructured and ad hoc in nature. 25. Adviser 2 was also critical of other aspects of record-keeping in that the recording of Miss A's behaviours was ineffective and inconsistent. A behaviour chart would have made the clinical picture clearer and enabled a more helpful analysis over time. It would also have provided data to inform clinical judgements on, for example, the prescription of medication and make the rationale for treatment decisions more transparent and justifiable. (a) Conclusion 26. Mrs C complained that the Board wrongly prescribed haloperidol to her aunt, Miss A. I have decided that it was reasonable for the Board to prescribe haloperidol to Miss A on medical grounds. In reaching my decision, I have taken into account the failures by the Board to meet Miss A's needs as a patient with sensory impairment and the impact this had on her behaviour. The Board could and should have done more to better manage Miss A's hearing impairment and aids. However, the advice I have accepted is that the prescription was in line with current best clinical practice in the management of delirium. There was evidence Miss A suffered from cognitive impairment and there was a valid concern that she was at risk of harming herself or others. In the circumstances, I do not uphold the complaint. 16 November 2011 27. Although I have not upheld Mrs C's complaint, I have serious concerns about the Board's actions in relation to the Act. The advice I have accepted is that it was likely Miss A lacked capacity to provide informed consent to treatment or participate in treatment decision-making during her admission to hospital in September 2009. The Board failed to assess her capacity, which is of concern. Had they done so and found, as the evidence suggested, that Miss A lacked capacity to consent to treatment, then they should have completed a certificate of incapacity and consulted Mrs C about treatment. Good communication with carers is an underpinning principle of the Act and ensures that patients receive a reasonable standard of care. Had the Board acted properly, which includes completing its own documents properly, healthcare professionals would have had a full and proper discussion with Mrs C about Miss A's needs and treatment decisions. This would have given healthcare professionals an opportunity to explain the risks and benefits of the use of drugs to control Mrs A's agitation and hostility, and Mrs C an opportunity to inform treatment decisions. 28. In conclusion, I did not find evidence that Miss A was wrongly prescribed haloperidol on medical grounds, but the Board failed to act within the Act when they provided treatment to Miss A. The Board said that an orthopaedic unit was not the best place for Miss A given her needs. However, as Adviser 1 pointed out, this is an issue pertinent to all areas of the NHS, not just those services that specialise in the care of patients with capacity issues. I have, therefore, made a number of recommendations. (a) Recommendations 29. I recommend that the Board: Completion date (i) carry out an audit of their practice on implementation of the Adults with Incapacity Act with particular reference to consent and report to the Ombudsman on the findings; (ii) amend its guidance on managing patients with delirium to include the requirements of the Adults with Incapacity Act; (iii) share this report with staff to ensure they complete forms properly and meet the communication needs of patients with cognitive or sensory (or both) 16 November 2011 (iv) apologise to Mrs C for the failures identified. (b) The Board failed to provide clarity surrounding the prescribing chain

of command

30. Mrs C complained that the Board said haloperidol was prescribed on the direct instruction of the psychiatric liaison nurse and queried whether the psychiatric liaison nurse had sufficient authority to prescribe medication and that this responsibility should lie with the doctor. Mrs C was later told that a doctor had prescribed with the medication and she complained that they had failed to provide clarity about the prescribing chain of command. Board's response 31. In the Board's first response to Mrs C's complaint, they said a consultant orthopaedic surgeon had reviewed Miss A's medical records and said that haloperidol had been prescribed on the direct instruction of the psychiatric liaison nurse. The psychiatric liaison nurse had been contacted by staff on 15 September 2009 who told him that Miss A's behaviour continued to be destructive and aggressive. He had reviewed Miss A on 28 August and 7 September 2009. The prescription was for 0.5 milligram of haloperidol to be administered twice a day instead of lorazepam. This dose was in accordance with the guidelines. When the psychiatric liaison nurse reviewed Miss A on 17 September 2009, he advised that the dose could be reduced if staff felt that she was over sedated. 32. In a further response, the Board said that the psychiatric liaison nurse was not licensed to prescribe medications, only to recommend them. The psychiatric liaison nurse frequently recommended haloperidol to medical staff in the management of patients whose behaviour was challenging so that nursing care could be carried out. The Board went on to say that haloperidol was prescribed by a junior doctor, who was fully qualified to do so. They were responsible for the day-to-day management of patients on wards and were expected to use a clinical judgement when prescribing medications. They did not have to discuss every change of medication with the registrar or consultant although they frequently sought advice from other specialities in managing conditions which were out with the orthopaedic speciality. Prolonged placement within an orthopaedic unit was not the best place to provide care to Miss A, but this was the only option due to the shortage of beds. 16 November 2011 Advice received 33. Adviser 1 said it was standard practice for nurses from a variety of disciplines to make recommendations regarding prescriptions. It was, however, for medical staff to decide whether or not to follow the recommendations. In this case, it was assumed that the medical professional who prescribed haloperidol was a first-year post-graduation doctor (FY1). They should discuss a prescription with a more senior medical colleague if they had any doubt about it, but it would be impractical to do so on every occasion. Adviser 1 went on to say that it was not unusual for an FY1 to have prescribed haloperidol, but that it would have been preferable if more senior medical advice had been taken and documented. This was because there was a suboptimal documentation of cognition and capacity and the failure to consider and complete documentation under the Act, which an FY1 could not complete on their own. Adviser 1 said that the Board's explanation about the prescribing chain of command was ultimately accurate and clear. (b) Conclusion 34. Mrs C complained that the Board had failed to provide clarity about the prescribing chain of command of haloperidol to Miss A. The Board initially told Mrs C that a psychiatric liaison nurse instructed staff to prescribe haloperidol, but later said that the psychiatric liaison nurse could only recommend the use of drugs and that the responsibility lay with the prescribing doctor. I can understand why the Board's use of 'instructed' was interpreted by Mrs C as saying that the responsibility for prescribing haloperidol lay with the psychiatric liaison nurse. However, the Board clarified their position and the advice I have accepted is that their explanation was ultimately clear. I do not uphold the 35. I note what Adviser 1 said about the FY1 in this instance seeking more senior medical advice. This will be addressed by the recommendations I made in paragraph 29. 36. The Board have accepted the recommendations and will act on them accordingly. The Ombudsman asks that the Board notify him when the recommendations have been implemented. 16 November 2011 Explanation of abbreviations used

The complainant's aunt Tayside NHS Board Ninewells Hospital The Ombudsman's medical adviser in care of the elderly The Ombudsman's clinical nursing adviser in mental health Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act Computerised tomography scan 16 November 2011 Glossary of terms

Cortical atrophy Degeneration of brain cells An antipsychotic drug A short to medium term tranquillising drug Small vessel ischaemic Small changes in the vessels bringing blood flow to the brain 16 November 2011 List of legislation and policies considered

Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000 16 November 2011

16 November 2011

Source: http://www.spso.org.uk/sites/spso/files/investigation_reports/2011.11.16%20201002867%20Tayside%20NHS%20Board.pdf

Appropriate timing of fluoxetine and statin delivery reduces the risk of secondary bleeding in ischemic stroke rats

JOURNAL OF NEUROLOGY AND NEUROSCIENCE Maria HH Balch, Appropriate Timing of Fluoxetine and Statin Moner A Ragas, Danny Delivery Reduces the Risk of Secondary Wright,Amber Hensley, Bleeding in Ischemic Stroke Rats Kenny Reynolds, Bryce Kerr and Adrian M Corbett Department of Neuroscience, Cell

Hydroxyurea clinical practice guidelines - providers - first choice by select health of south carolina

Tips and guidelines for prescribing hydroxyurea. Clinical Practice Guidelines • 15mg/kg daily for adult patients with normal kidney function. • 5-10mg/kg daily for adult patients with creatinine clearance (CrCl) <60 mL/min. • 20mg/kg daily for infants (>9 months) and Baseline laboratory values • Complete blood count (CBC) with differential.